Tag: Ursula K. Le Guin

-

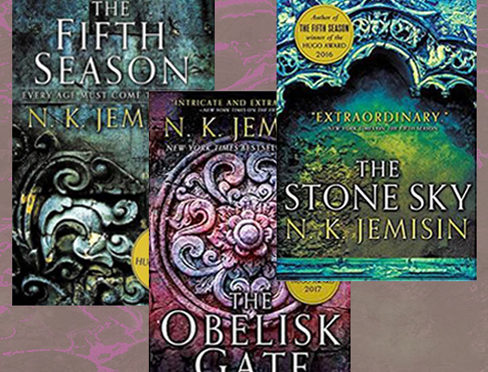

The Broken Earth Trilogy —and why it should win a third straight Hugo for N. K. Jemisin

Reading each volume of The Broken Earth trilogy by N. K. Jemisin left me electrified. The first two books, The Fifth Season and The Obelisk Gate, won the past two annual Hugo awards for best novel—a rare occurrence. Her final book in the series, The Stone Sky, is up for…

-

Ursula K. Le Guin: Telling makes the world

Maria Popova has written on her wonderful website Brain Pickings about Ursula K. Le Guin’s essay on the nature of speech, “Telling is Listening.” This brought back to me the sense of how much Le Guin—a master storyteller herself—has made the importance of storytelling a central theme in many of her novels…