Tag: Octavia Butler

-

Blobs, Orbs, and Starfish: Really Alien Aliens

Book blogger Shruti Ramanujam recently published a list of “oddly specific storylines” she loves in books, that made me laugh out loud. And it made me think about what storylines or tropes attract me in a book. One of those tropes, for me, is “really alien aliens.” I find them fascinating, and…

-

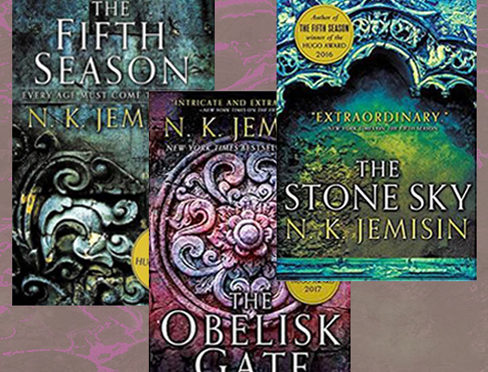

The Broken Earth Trilogy —and why it should win a third straight Hugo for N. K. Jemisin

Reading each volume of The Broken Earth trilogy by N. K. Jemisin left me electrified. The first two books, The Fifth Season and The Obelisk Gate, won the past two annual Hugo awards for best novel—a rare occurrence. Her final book in the series, The Stone Sky, is up for…