Tag: climate fiction

-

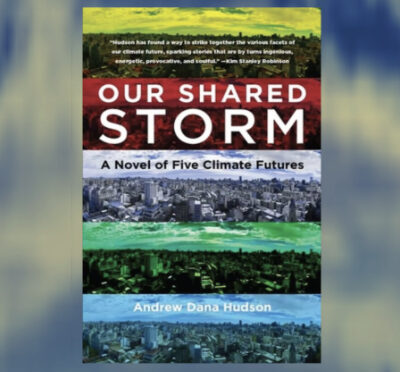

Our Shared Futures

Can climate fiction help us see our way through the maze of possible futures we face? Can it help us move forward from our present moment? Andrew Dana Hudson’s slim novel, Our Shared Storm: A Novel of Five Climate Futures, engages these questions directly, by imagining how four characters’ lives would…