Category: Visual art

-

Talking with Diane Burko on art and climate change

My conversation with climate artist Diane Burko was posted on Creative Disturbance, a podcasting platform for dialogue among artists and scientists on sustainability and environmental issues. We’re happy to join others on their Art & Earth Sciences channel, shining different lights on urgent issues relating to climate change—especially this week, as the…

-

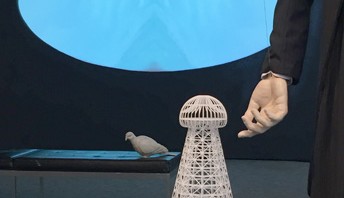

An elegy for Tesla

Jeanne Jaffe’s ambitious Elegy for Tesla is a high-tech, dreamlike and heartfelt meditation on Nikola Tesla, the legendary scientist and inventor. Jaffe’s multimedia installation fills the Rowan University Art Gallery with videos and sound, 3‑D printed models of his iconic inventions, and animatronic, motion-activated figures of Tesla that move and, in…

-

Phillips & Healy, sparkling

Carolyn Healy and John Phillips have done it again: they’ve created an art installation piece that both transforms the space it’s housed in, and crystallizes some essence of the place. This time they did it inside a one-room schoolhouse on the grounds of WheatonArts in Millville, New Jersey, a nationally known center for…

-

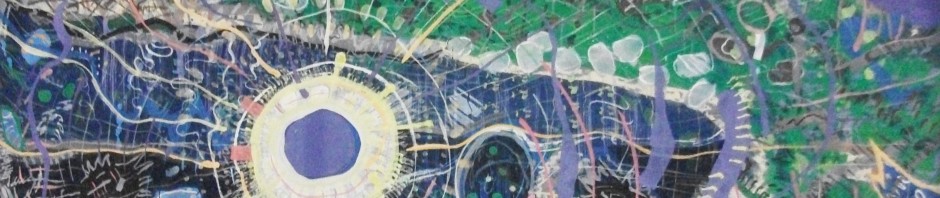

Burchfield and synesthesia

In the paintings of Charles Burchfield, the trees vibrate, the air pulses with rhythmic patterns, and birdsong takes on shape and color. Everything is alive, even a dead branch, even a house. At the major exhibit of Burchfield’s work at the Brandywine River Museum, up through November 16, you can see the…

-

Seeing Turrell’s Skyspace

My friend and I arrived at James Turrell’s Skyspace, at Philadelphia’s Chestnut Hill Friends Meetinghouse, just before sundown. When I asked another visitor if we could take photos, the man—who had visited a number of times before—told us the artist had asked that no one take pictures, so that we could keep the…

-

James Turrell and sacred architecture

James Turrell’s installations at the Guggenheim left me in an altered state. Using light as his primary medium, Turrell’s art requires slow looking and an active acceptance of ambiguity—both conducive to entering a kind of contemplative trance. He’s pursued his singular work, from early experiments with slide projectors in dark rooms…

-

From the Ground Up

“Like embedded journalists, Peter Kinney, Isaiah Zagar and Jeff Waring have made the work in this show as ‘embedded’ artists, burrowing deep into the natural world to bring back its dirty, messy, mysterious secrets… Each of these artists is after full-on communion with the natural world, the kind that leaves…