Category: Nikola Tesla

-

Tesla’s Opera has a cover!

Tesla’s Opera: The Real, Stranger-than-fiction Nikola Tesla is moving toward publication! We now have a cover design for the book I’m editing, which uses the opera inspired by Nikola Tesla’s life as a door to widening our understanding of the visionary inventor. The opera Violet Fire, with a score by composer Jon Gibson…

-

Celebrating Tesla

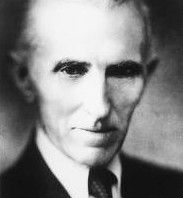

An opera turns into a book Years ago I became entranced by the visionary inventor, Nikola Tesla, and I began to imagine his extraordinary life as an opera. It seemed to me that only an opera, with its grand scale and intense passions, could do justice to Tesla. Tesla (1856–1943) helped create the bedrock…

-

Elephants and Radium Girls Electricity and Complicity in Brooke Bolander’s The Only Harmless Great Thing

In The Only Harmless Great Thing, Brooke Bolander has taken on two strange and disturbing events from the early 20th century: the willfully negligent poisoning of young women painting radium-tinged watch dials for the United States Radium Company, and the public electrocution of Topsy the elephant at Coney Island in…

-

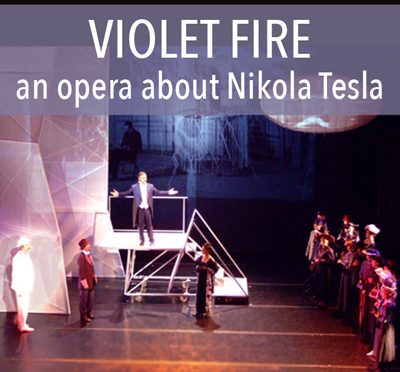

Tesla, recorded

Violet Fire, the opera about Nikola Tesla that I worked on as librettist with composer Jon Gibson, is finally getting a studio recording! It’s a little late—the world premiere and U.S. premiere happened in Belgrade and New York in 2006—but I’m still excited. Last week, Jon convened a stellar group of musicians at a recording…

-

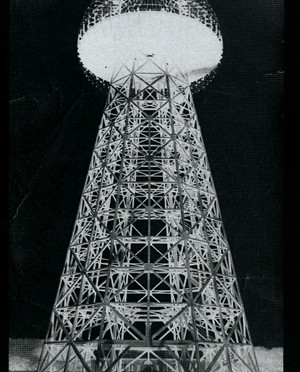

Living Tesla’s Dream

Today is the 160th anniversary of Nikola Tesla’s birth. Tesla was a seer of electricity, whose vision of a world transformed with an electric grid powered by his alternating current system surely seemed like a wild dream in the late 19th century. Tesla is claimed as a hero in both Serbia and Croatia, having…

-

Tesla in Bankruptcy

On March 18, 1916—one hundred years ago today—the New York World ran an article with the headline: “Tesla No Money Wizard; Swamped by Debts, He Vows.” The news followed a court filing that revealed the great inventor, Nikola Tesla, had no assets and owed thousands in back rent to the Waldorf…

-

An elegy for Tesla

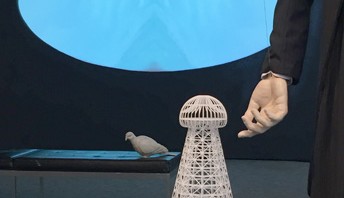

Jeanne Jaffe’s ambitious Elegy for Tesla is a high-tech, dreamlike and heartfelt meditation on Nikola Tesla, the legendary scientist and inventor. Jaffe’s multimedia installation fills the Rowan University Art Gallery with videos and sound, 3‑D printed models of his iconic inventions, and animatronic, motion-activated figures of Tesla that move and, in…

-

Mark Twain & Crowdfunding

I’ve just written a guest post for The Head & The Hand Press, considering how Mark Twain’s innovations in publishing could be seen as a precursor to the growing trend of crowdfunding for books. Twain/Clemens thought outside the box not only in his writing, but in the business of books. Twain’s passion for innovation…

-

Gravity and the Noosphere

I loved seeing Gravity. In my opinion, the Planet Earth should be nominated for a supporting-player Oscar. I drank in the massive, stunning views of the earth in the background of so many scenes—completely convincing, thanks to high-level CGI effects. At those screen-filling distances, you could make out the thin, blue-white film…

-

How Tesla kidnapped my imagination

There’s something about the inventor Nikola Tesla that has strongly attracted artists—much more than his arch-rival Edison, let’s say. Tesla’s amazing life and grand visions have pulled artistic creations from those he captivates—a stream of operas, music, plays, novels and stories, film and video. I know about this firsthand, because it…