Category: New Opera & Performance

-

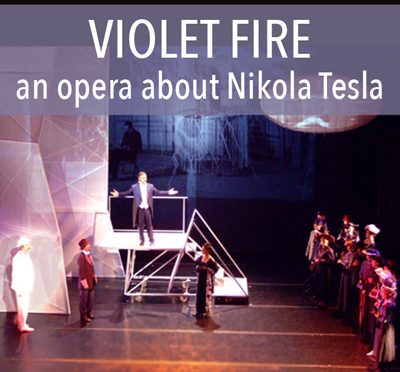

Nikola Tesla’s extraordinary love story

Most people know Nikola Tesla as an inventor. His breakthroughs in electricity and wireless transmission helped to transform our world; that’s why his name is associated with a well-known electric car (more about that later). But Tesla’s visionary side didn’t just express itself in the world-changing inventions he imagined into being. He…

-

Tesla’s Opera has a cover!

Tesla’s Opera: The Real, Stranger-than-Fiction Nikola Tesla is moving toward publication! We now have a cover design for the book , which uses the opera inspired by Nikola Tesla’s life as a door to widen our understanding of the visionary inventor. The opera Violet Fire, with a score by composer Jon Gibson and…

-

Celebrating Tesla

An opera turns into a book Years ago I became entranced by the visionary inventor, Nikola Tesla, and I began to imagine his extraordinary life as an opera. It seemed to me that only an opera, with its grand scale and intense passions, could do justice to Tesla. Tesla (1856–1943) helped create the bedrock…

-

Doctor Atomic’s blast zone

The latest production ofDoctor Atomic, the opera about the birth of the Nuclear Age by composer John Adams and director/librettist Peter Sellars, saw it coming “home” to New Mexico, where the story is set. In the process, it became a stunning, unrepeatable artistic event. I was lucky to see one of the…

-

Tesla, recorded

Violet Fire, the opera about Nikola Tesla that I worked on as librettist with composer Jon Gibson, is finally getting a studio recording! It’s a little late—the world premiere and U.S. premiere happened in Belgrade and New York in 2006—but I’m still excited. Last week, Jon convened a stellar group of musicians at a recording…

-

Leah Stein, Dance Alchemist

Leah Stein, a master of site-specific choreography, is known for creating outdoor dances that work a kind of alchemy on the places where they happen. She proceeds inclusively, allowing her dancers, the audience, the place itself, and random elements including passersby and even the weather, to come together into a new kind of…

-

More women in opera?

With all the great women’s roles in opera, from Aida to Norma to Tosca, bringing up the issue of increasing women’s role in opera could seem like begging the question. Or like the setup for a punch line—how many sopranos do you need to put on an opera? But at the…

-

Remembering Sun Ra

Space is the Place—the wild space-fantasy film starring Sun Ra, the legendary experimental jazz artist—came out in 1974. It follows Sun Ra and his Arkestra as they travel to another planet, where they hope to create an off-earth home for African Americans. Back on Earth, they do battle with a pimp-overlord…

-

Opera, Real and Surreal

“Opera permits us to go into a world that is not real.” This was spoken by Nicole Paiement, artistic director of Opera Parallèle, about halfway through a panel discussion of storytelling in opera at Opera America’s New Works Forum, held last week in New York. I was there because Judgment of Midas, the…

-

How Tesla kidnapped my imagination

There’s something about the inventor Nikola Tesla that has strongly attracted artists—much more than his arch-rival Edison, let’s say. Tesla’s amazing life and grand visions have pulled artistic creations from those he captivates—a stream of operas, music, plays, novels and stories, film and video. I know about this firsthand, because it…

-

Midas in Milwaukee

Judgment of Midas premiered in Milwaukee last week, and I’m still buzzing. It was an incredible experience. Kevin Stalheim, who leads Present Music, and Jill Anna Polasek of Milwaukee Opera Theater, succeeded in making this wonderful production feel like an opera, even though it was “semi-staged.” Kamran Ince, the composer,…

-

Touching on Midas

It’s just a week now before the premiere of Judgment of Midas, the opera I’ve been working on with Kamran Ince. It’s happening in Milwaukee, in a production with Present Music and the Milwaukee Opera Theater. I’m really excited, looking forward to seeing how it’s been imagined, and hearing the complete score…