Category: Myth + Spirituality

-

Reclaiming the Monster

Women can be monsters too. From snake-haired Medusa to the horrifying mama-alien of the Alien movies, female monsters have often embodied male fears of women’s unchecked power. So it makes sense that women writers and artists have been changing the perspective on these archetypes. In her 2022 book Women and…

-

Elephants and Radium Girls Electricity and Complicity in Brooke Bolander’s The Only Harmless Great Thing

In The Only Harmless Great Thing, Brooke Bolander has taken on two strange and disturbing events from the early 20th century: the willfully negligent poisoning of young women painting radium-tinged watch dials for the United States Radium Company, and the public electrocution of Topsy the elephant at Coney Island in…

-

Doctor Atomic’s blast zone

The latest production ofDoctor Atomic, the opera about the birth of the Nuclear Age by composer John Adams and director/librettist Peter Sellars, saw it coming “home” to New Mexico, where the story is set. In the process, it became a stunning, unrepeatable artistic event. I was lucky to see one of the…

-

Thinking about Gaia

In this month of Earth Day and marching for science and climate, I’m thinking about Gaia. A hashtag popped up on Twitter last week: #ifonlytheearthcouldspeak. Yes! That’s a good prompt to contemplate right now. The hashtag elicited a range of responses from funny and snarky to thoughtful and earnest. Some tweeters suggested that…

-

The radical leaps of A Wrinkle in Time

I was in sixth grade when I was swept up in the world of A Wrinkle in Time, part of the first generation of girls to discover it. Madeleine L’Engle’s novel imprinted itself on my imagination and gave me a sense of what speculative fiction could be, before I had read much science fiction.…

-

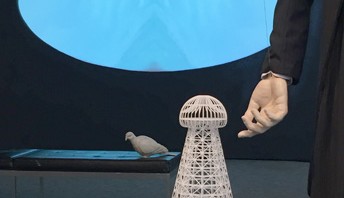

An elegy for Tesla

Jeanne Jaffe’s ambitious Elegy for Tesla is a high-tech, dreamlike and heartfelt meditation on Nikola Tesla, the legendary scientist and inventor. Jaffe’s multimedia installation fills the Rowan University Art Gallery with videos and sound, 3‑D printed models of his iconic inventions, and animatronic, motion-activated figures of Tesla that move and, in…