Category: Books

-

Celebrating Tesla

An opera turns into a book Years ago I became entranced by the visionary inventor, Nikola Tesla, and I began to imagine his extraordinary life as an opera. It seemed to me that only an opera, with its grand scale and intense passions, could do justice to Tesla. Tesla (1856–1943) helped create the bedrock…

-

Reclaiming the Monster

Women can be monsters too. From snake-haired Medusa to the horrifying mama-alien of the Alien movies, female monsters have often embodied male fears of women’s unchecked power. So it makes sense that women writers and artists have been changing the perspective on these archetypes. In her 2022 book Women and…

-

Blobs, Orbs, and Starfish: Really Alien Aliens

Book blogger Shruti Ramanujam recently published a list of “oddly specific storylines” she loves in books, that made me laugh out loud. And it made me think about what storylines or tropes attract me in a book. One of those tropes, for me, is “really alien aliens.” I find them fascinating, and…

-

Elephants and Radium Girls Electricity and Complicity in Brooke Bolander’s The Only Harmless Great Thing

In The Only Harmless Great Thing, Brooke Bolander has taken on two strange and disturbing events from the early 20th century: the willfully negligent poisoning of young women painting radium-tinged watch dials for the United States Radium Company, and the public electrocution of Topsy the elephant at Coney Island in…

-

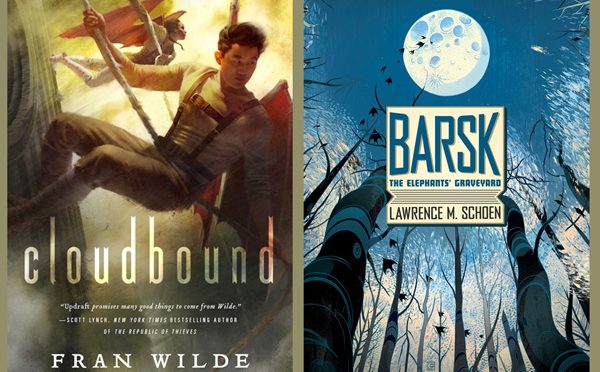

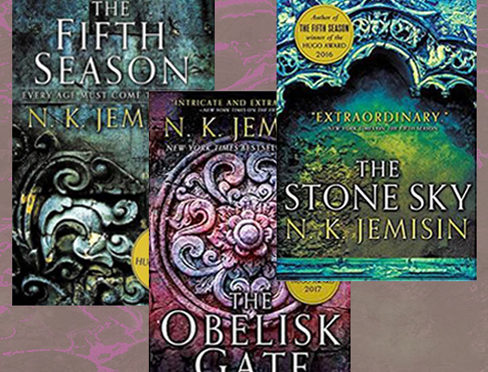

The Broken Earth Trilogy —and why it should win a third straight Hugo for N. K. Jemisin

Reading each volume of The Broken Earth trilogy by N. K. Jemisin left me electrified. The first two books, The Fifth Season and The Obelisk Gate, won the past two annual Hugo awards for best novel—a rare occurrence. Her final book in the series, The Stone Sky, is up for…

-

Coming out as a Fan

It’s time for me to come out as a member of sci-fi fandom. I love science fiction and fantasy. I’ve read the books, watched the shows, and seen the movies. I’ve attended Cons. And yes, I have worn Vulcan ears. It’s time, because my novel, The Speed of Clouds, which is coming out…

-

Thinking about Gaia

In this month of Earth Day and marching for science and climate, I’m thinking about Gaia. A hashtag popped up on Twitter last week: #ifonlytheearthcouldspeak. Yes! That’s a good prompt to contemplate right now. The hashtag elicited a range of responses from funny and snarky to thoughtful and earnest. Some tweeters suggested that…

-

An Alternate History reading list for this moment Or, Did Philip K. Dick foresee our current predicament?

Are we living in an alternate branch of history? I’ve been asking myself that question since waking up the morning of November 9, with the feeling that reality had turned sideways. Since then, many of us have shared the stages of shock, denial, anger and sadness that come after a great…

-

Ursula K. Le Guin: Telling makes the world

Maria Popova has written on her wonderful website Brain Pickings about Ursula K. Le Guin’s essay on the nature of speech, “Telling is Listening.” This brought back to me the sense of how much Le Guin—a master storyteller herself—has made the importance of storytelling a central theme in many of her novels…

-

The radical leaps of A Wrinkle in Time

I was in sixth grade when I was swept up in the world of A Wrinkle in Time, part of the first generation of girls to discover it. Madeleine L’Engle’s novel imprinted itself on my imagination and gave me a sense of what speculative fiction could be, before I had read much science fiction.…

-

Kate Atkinson and quantum physics

Kate Atkinson has now won the Costa Book Award twice in the past three years—for her companion novels, A God in Ruins (2015) and the stunning Life After Life (2013). To celebrate, here are my thoughts on the first one, which I just finished. Life after Life can be seen as a kind of…